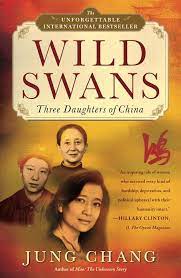

wild swans | jung chang

This book changed my life. I was born in China and grew up in Canada an only child. Jung Chang’s Wild Swans helped me better understand my mother, my family, the country we are all from, and ultimately myself. This, my favorite passage, revealed to me how profoundly not-alone I was:

I was extremely sad to see the lovely plants go. But I did not resent Mao. On the contrary, I hated myself for feeling miserable. By then I had grown into the habit of “self-criticism” and automatically blamed myself for any instincts that went against Mao’s instructions. In fact, such feelings frightened me. It was out of the question to discuss them with anyone. Instead, I tried to suppress them and acquire the correct way of thinking. I lived in a state of constant self-accusation.

Such self-examination and self-criticism were a feature of Mao’s China. You would become a new and better person, we were told. But all this introspection was really designed to serve no other purpose than to create a people who had no thoughts of their own.

notes:

When he asked my grandmother if she would mind being poor, she said she would be happy just to have her daughter and himself: “If you have love, even plain cold water is sweet.”

She was a pious Buddhist and every day in her prayers asked Buddha not to reincarnate her as a woman. “Let me become a cat or a dog, but not a woman,” was her constant murmur as she shuffled around the house, oozing apology with every step.

But my mother felt he was shallow. She noticed that he never went to Peking, but lounged around at home enjoying the life of a dilettante. One day she discovered he had not even read The Dream of the Red Chamber, the famous eighteenth-century Chinese classic, with which every literate Chinese was familiar. When she showed how disappointed she felt, young Liu said airily that the Chinese classics were not his forte, and that what he actually liked most was foreign literature. To try to reassert his superiority, he added: “Now, have you read Madame Bovary? That’s my all-time favorite. I consider it the greatest of Maupassant’s works.”

My mother had read Madame Bovary—and she knew it was by Flaubert, not Maupassant. This vain sally put her off Liu in a big way, but she refrained from confronting him there and then—to do so would have been considered “shrewish.”

Immediately after this, the family members burst out crying. From then to the day of the burial, on the forty-ninth day after the death, the sound of weeping and wailing was supposed to be heard nonstop from early morning until midnight, accompanied by the constant burning of artificial money for the deceased to use in the other world. Many families could not keep up this marathon, and hired professionals to do the job for them.

In addition she said, “Who ever heard of a girl rejecting a man because he got the name of some foreign writer wrong, or because he had affairs? All rich young men like to have fun and sow their wild oats. Besides, you have no need to worry about concubines and maids. You’re a strong character; you can keep your husband under control.”

Her father took his hand and said: “Try to be a scholar, or run a small business. Never try to be an official. It will ruin you, the way it has ruined me.” These were his last words to his family.

She soon settled on a woman who was three years older than him and came from a poor family, which meant she would be hardworking and capable.

He sat calmly on the kang in the corner of his room by the window and prayed silently to the Buddha. At one point fourteen kittens ran into the room. He was delighted: “A place a cat tries to hide in is a lucky place,” he said. Not a single bullet came into his room—and all the kittens survived.

A voice answered: “We are the people’s army. We have come to liberate you.” … “Don’t be afraid,” they said. “We won’t harm you. We are your army, the people’s army.” They said they wanted to check the house for Kuomintang soldiers. It was not a request, though it was put politely. The soldiers did not turn the place upside down, nor did they ask for food or steal anything. After the search they left, bidding the family a courteous farewell.

One of the top commanders who had been caught had his daughter with him; she was in an advanced stage of pregnancy. He asked the Communist commanding officers if he could stay in Jinzhou with her. The Communist officer said it was not convenient for a father to help his daughter deliver a baby, and that he would send a “woman comrade” to help her. The Kuomintang officer thought he was only saying this to get him to move on. Later on he learned that his daughter had. been very well treated, and the “woman comrade” turned out to be the wife of the Communist officer. Policy toward prisoners was an intricate combination of political calculation and humanitarian consideration, and this was one of the crucial factors in the Communists’ victory. Their goal was not just to crush the opposing army but, if possible, to bring about its disintegration. The Kuomintang was defeated as much by demoralization as by firepower.

Chiang Kai-shek had to consent, albeit halfheartedly, since he knew this would allow the Communists to survive and develop. “The Japanese are a disease of the skin,” he said, “the Communists are a disease of the heart.”

Harbin was largely built by Russians and was known as “the Paris of the East” because of its broad boulevards, ornate buildings, smart shops, and European-style cafés.

He told her that she must be strong, and that as a young student “joining the revolution” she needed to “go through the five mountain passes”—which meant adopting a completely new attitude to family, profession, love, lifestyle, and manual labor, through embracing hardship and trauma.

When Mao’s short proclamation was over, she and her comrades burst into cheers and threw their caps in the air—a gesture the Chinese Communists had learned from the Russians.

This was an important occasion. In Chinese tradition the person with the most power over a married woman was always her mother-in-law, to whom she had to be completely obedient and who would tyrannize her. When she in turn became a mother-in-law, she would bully her own daughter-in-law in the same way. Liberating daughters-in-law was an important Communist policy, and rumors abounded that Communist daughters-in-law were arrogant dragons, ready to boss their mothers-in-law around. Everyone was on tenterhooks waiting to see how my mother would behave.

It was unthinkable for a peasant woman to take a rest if she was pregnant. She worked right up to the moment of delivery, and there were innumerable stories about women cutting the umbilical cord with a sickle and carrying on. Mrs. Mi had borne her own baby on a battlefield and had had to abandon it on the spot—a baby’s cry could have endangered her whole unit.

She had heard about the Sichuan character, which was supposed to be as saucy and spicy as the food.

The Party’s all-around intrusion into people’s lives was the very point of the process known as “thought reform.” Mao wanted not only external discipline, but the total subjection of all thoughts, large or small. Every week a meeting for “thought examination” was held for those “in the revolution.” Everyone had to both criticize themselves for incorrect thoughts and be subjected to the criticism of others.

The government decided to build a road south to the province of Yunnan. In only one year, using no machinery at all, they built over eighty miles through a very hilly area, with numerous rivers. The labor force was made up of peasants, who worked in exchange for food.

Traditionally, square shoulders were regarded as unbecoming for girls, so my shoulders were bound tightly to make them grow into the required slopy shape. This made me bawl so loudly that my nurse would release my arms and shoulders, allowing me to wave at people who came to the house, and clutch them, which I liked doing from an early age. My mother always attributed my outgoing character to the fact that she was happy when she was pregnant with me.

For the first time she vaguely reflected on the fact that, as the revolution was made my human beings, it was burdened with their failings. But it did not occur to her that the revolution was doing very little to deal with these failings, and actually relied on some of them, often the worst.

Saturday was the only day married couples were allowed to spend together. Among officials, the euphemism for making love was “spending a Saturday.” Gradually, this regimented lifestyle relaxed a bit and married couples were able to spend more time together, but almost all still lived and spent most of their time in their office compounds.

This signaled the beginning of the end of individual expression in China. All the media had been taken over by the Party when the Communists came to power. From now on it was the minds of the entire nation that were placed under ever tighter control.

Like other detainees, my mother was assigned various women “companions” who followed her everywhere, even to the toilet, and slept in the same bed with her. She was told that this was for her protection. She understood implicitly that she was being “protected” from committing suicide, or trying to collude with anyone else.

But then she began to persuade herself that she should not resent the Party for trying to maintain its purity. In China, one was accustomed to a certain amount of injustice. Now, at least, it was for a worthy cause. She also repeated to herself the Party’s words when it demanded sacrifice from its members: “You are going through a test, and suffering will make you a better Communist.”

It was not customary for a father to hold his children in his arms, or to show affection by kissing them or embracing them. He would often give the boys piggyback rides, and would pat their shoulders or stroke their hair, which he rarely did to us girls. When we got beyond the age of three he would lift us carefully with his hands under our armpits, strictly adhering to Chinese convention, which prescribed avoiding intimacy with one’s daughters. He would not come into the room where my sister and I slept without our permission.

Whenever she had time she would cuddle us, gently scratching or tickling us, especially on our elbows, which was intensely pleasurable. Pure heaven for me was putting my head on her lap and having the inside of my ears tickled. Ear-picking was a traditional form of pleasure for the Chinese. As a child, I remember seeing professionals carrying a stand with a bamboo chair on one end and scores of tiny fluffy picks dangling from the other.

My mother could see that as far as my father’s relationship with the Party was concerned, she was an outsider. One day, when she ventured some critical comments about the situation and got no response from him, she said bitterly, “You are a good Communist, but a rotten husband!” My father nodded. He said he knew.

This absurd situation reflected not only Mao’s ignorance of how an economy worked, but also an almost metaphysical disregard for reality, which might have been interesting in a poet, but in a political leader with absolute power was quite another matter. One of its main components was a deep-seated contempt for human life. Not long before this he had told the Finnish ambassador, “Even if the United States had more powerful atom bombs and used them on China, blasted a hole in the earth, or blew it to pieces, while this might be a matter of great significance to the solar system, it would still be an insignificant matter as far as the universe as a whole is concerned.”

It was a time when telling fantasies to oneself as well as others, and believing them, was practiced to an incredible degree. … A large part of the population was swept into this confused, crazy world. “Self-deception while deceiving others” (zi-qi-qi-ren) gripped the nation. Many people—including agricultural scientists and senior Party leaders—said they saw the miracles themselves. Those who failed to match other people’s fantastic claims began to doubt and blame themselves.

There was no corruption in the sense of officials hoarding grain. Party officials were only marginally better off than the ordinary people. In fact, in some villages they themselves starved first—and died first. The famine was worse than anything under the Kuomintang, but it looked different: in the Kuomintang days, starvation took place alongside blatant unchecked extravagance.

Throughout history Chinese scholars and mandarins had traditionally taken up fishing when they were disillusioned with what the emperor was doing. Fishing suggested a retreat to nature, an escape from the politics of the day. It was a kind of symbol for disenchantment and noncooperation.

I was terribly proud to be seen in their company, as actors and actresses were endowed with tremendous glamour in China. They enjoyed special tolerance and were allowed to dress more flamboyantly than other people, and even to have affairs.

In our elite hall there were more restricted films which were not shown to anyone else, even the staff in the big auditorium. These were called “reference films” and were made up mostly of clips of films from the West. This was the first time I ever saw a miniskirt—or the Beatles. …

I was baffled by the way the Western workers were dressed—in neat suits that were not even patched, a far cry from my idea of what the oppressed masses in a capitalist country ought to be wearing. After the film I asked my mother about this and she said something about “relative living standards.” I did not understand what she meant, and the question remained with me.

As a child, my idea of the West was that it was a miasma of poverty and misery, like that of the homeless Little Match Girl in the Hans Christian Andersen story. When I was in the boarding nursery and did not want to finish my food, the teacher would say: “Think of all the starving children in the capitalist world!” In school, when they were trying to make us work harder, the teachers often said: “You are lucky to have a school to go to and books to read. In the capitalist countries children have to work to support their hungry families.”

…I thought how nice it would be to swap my commonplace old wax-paper umbrella for [a raincoat]. But I immediately castigated myself for this “bourgeois” tendency, and wrote in my diary: “Think of all the children in the capitalist world—they can’t even think of owning an umbrella!”

Foreigners said “hello” all the time, with an odd intonation. I did not know what “hello” meant; I thought it was a swear word. When boys played “guerrilla warfare,” which was their version of cowboys and Indians, the enemy side would have thorns glued onto their noses and say “hello” all the time.

The first time I ever heard about rape was reading about one attributed to a foreign priest in a novel. Priests also invariable appeared as imperialist spies and evil people who used babies from orphanages for medical experiments.

[My brother] began to feel that school, the media, and adults in general could not be trusted when they said that the capitalist world was hell and China was paradise.

We saw only affection between our parents, never their quarrels.

The essence of these two complementary slogans[—“Serve the People” and “Never Forget Class Struggle”—]was illustrated in Lei Feng’s poem “The Four Seasons,” which we all learned by heart:

Like spring, I treat my comrades warmly.

Like summer, I am full of ardor for my

revolutionary work.

I eliminate my individualism as an autumn

gale sweeps away fallen leaves,

And to the class enemy, I am cruel and ruthless

like harsh winter.

To show us what life without Mao would be like, every now and then the school canteen cooked something called a “bitterness meal,” which was supposed to be what poor people had to eat under the Kuomintang. It was composed of strange herbs, and I secretly wondered whether the cooks were playing a practical joke on us—it was truly unspeakable. The first couple of times I vomited.

A popular song went: “Father is close, Mother is close, but neither is as close as Chairman Mao.”

I was extremely sad to see the lovely plants go. But I did not resent Mao. On the contrary, I hated myself for feeling miserable. By then I had grown into the habit of “self-criticism” and automatically blamed myself for any instincts that went against Mao’s instructions. In fact, such feelings frightened me. It was out of the question to discuss them with anyone. Instead, I tried to suppress them and acquire the correct way of thinking. I lived in a state of constant self-accusation.

Such self-examination and self-criticism were a feature of Mao’s China. You would become a new and better person, we were told. But all this introspection was really designed to serve no other purpose than to create a people who had no thoughts of their own.

Traffic was in confusion for several days. For red to mean “stop” was considered impossibly counterrevolutionary. It should of course mean “go.” And traffic should not keep to the right, as was the practice, it should be on the left. … In the end, the old rules reasserted themselves, owing to Zhou Enlai, who managed to convince the Peking Red Guard leaders. But the youngsters found justifications for this: I was told by a Red Guard in my school that in Britain traffic kept to the left, so ours had to keep to the right to show our anti-imperialist spirit. She did not mention America.

I had my purse in a pocket of my jacket, and because of my climbing position it was quite visible. With two fingers, the boy picked it out. He had presumably chosen the moment of departure to snatch it. I burst out crying. The boy paused. He looked at me, hesitated, and put the purse back. Then he took hold of my right leg and hoisted me up. I landed on the table as the train was beginning to pick up speed.

Because of this incident, I developed a soft spot for adolescent pickpockets. In the coming years of the Cultural Revolution, when the economy was in a shambles, theft was widespread, and I once lost a whole year’s food coupons. But whenever I heard that policemen or other custodians of “law and order” had beaten a pickpocket, I always felt a pang. Perhaps the boy on that winter platform had shown more humanity than the hypocritical pillars of society.

The whole country was like a pressure cooker in which a gigantic head of compressed steam had built up. There were no football matches, pressure groups, law suits, or even violent films. It was impossible to voice any kind of protest about the system and its injustices, unthinkable to stage a demonstration. Even talking about politics—an important form of relieving pressure in most societies—was taboo.

In the meantime, they said, he must burn the rest of his collection.

When I came home that afternoon, I found my father in the kitchen. He had lit a fire in the big cement sink, and was hurling his books into the flames. This was the first time in my life I had seen him weeping. It was agonized, broken, and wild, the weeping of a man who was not used to shedding tears. Every now and then, in fits of violent sobs, he stamped his feet on the floor and banged his head against the wall.

I was so frightened that for some time I did not dare to do anything to comfort him. Eventually I put my arms around him and held him from the back, but I did not know what to say. He did not utter a word either. My father had spent every spare penny on his books. They were his life. After the bonfire, I could tell that something had happened to his mind.

My parents could not go out for relaxation either. “Relaxation” had become an obsolete concept: books, paintings, musical instruments, sports, cards, chess, teahouses, bars—all had disappeared. The parks were desolate, vandalized wastelands in which the flowers and the grass had been uprooted and the tame birds and goldfish killed. Films, plays, and concerts had all been banned: Mme. Mao had cleared the stages and the screens for the eight “revolutionary operas” which she had had a hand in producing, and which were all anyone was allowed to put on. In the provinces, people did not dare to perform even these. One director had been condemned because the makeup he had put on the tortured hero of one of the operas was considered by Mme. Mao to be excessive. He was thrown into prison for “exaggerating the hardship in the revolutionary struggle.” We hardly even thought of going out for a walk. The atmosphere outside was terrifying, with the violent street-corner denunciation meetings and all the sinister wall posters and slogans; people were walking around like zombies, with harsh or cowed expressions on their faces. What was more, my parents’ bruise faces marked them as condemned, and if they went out they ran the risk of being abused.

When I bumped into them in the mornings, they always gave me a very kind smile, which told me they were happy. I realized then that when people are happy they become kind.

He had always given the Party and the revolution priority over her. But my mother had understood and respected my father—and had above all never ceased to love him. She would particularly stand by him now that he was in trouble. No amount of suffering could bring her to denounce him.

In those days, beauty was so despised that my family was sent to this lovely house as a punishment.

I was to encounter a similar attitude again and again. Whenever I went out of the imposing gate of our courtyard, I was always aware of the stares from people on Meteorite Street, stares which were a mixture of curiosity and awe. It was clear to me that the general public regarded the Revolutionary Committees, rather than the capitalist-roaders, as transient.

What exactly they were supposed to educate us in was not made specific, but Mao always maintained that people with some education were inferior to illiterate peasants, and needed to reform to be more like them. One of his sayings was: “Peasants have dirty hands and cowshit-sodden feet, but they are much cleaner than intellectuals.”

The moral of this legend was that to conquer a people, one must conquer their hearts and minds—a strategy to which Mao and the Communists subscribed. I vaguely mused that this was why we had to go through “thought reform”—so that we would follow orders willingly. That was why peasants were set up as models: they were the most unquestioning and submissive subjects. On reflection today, I think the variant of Nixon’s adviser Charles Colson spelled out the hidden agenda: When you have them by the balls, their hearts and minds will follow.

I told myself it was despicable to have had any happy feelings at all, by the side of what I now realized was my grandmother’s deathbed. I resolved never to have a boyfriend again. Only by self-denial, I thought, could I expiate some of my guilt.

…Once I passed [Wen] on the street, and looked straight through him, catching only a glimpse of his eyes, in which I saw confusion and hurt. …

One day … Wen heard the alarm which signaled that American planes were coming. He was the first to leap up and charge out, but in his inexperience he stepped on a mine which his comrades had planted themselves. He was blown to smithereens. My last memory of him is his perplexed and wounded eyes watching me from a muddy street corner in Chengdu.

Some peasants talked about childhoods of unrelieved hunger, and lamented that their own children were so spoiled that they often had to be coaxed to finish their food.

This was Mao’s way: to keep “enemy” figures among the people so they always had someone visible and at hand to hate.

As for girls, the peasants considered it a complete waste of time for them to go to school. “They get married and belong to other people. It’s like pouring water on the ground.”

All these misfortunes were told to me without much drama or emotion. Here it seemed that even shocking deaths were like a stone being dropped into a pond where the splash and the ripple closed over into stillness in no time.

But I was attracted by something I had rarely come across in China—the logic that ran through an argument. Reading Marx helped me to think rationally and analytically.

On 26 June 1965 [Mao] made the remark which became a guideline for health and education: “The more books you read, the more stupid you become.” I went to work [as a doctor] with absolutely no training.

At night, lying on her straw mattress, [my mother] thought back over her children’s early years. She realized that there was not an awful lot of family life to remember. She had been an absentee mother when we were growing up, having submitted herself to the cause at the cost of her family. Now she reflected with remorse on the pointlessness of her devotion. She found she missed her children with a pain which was almost unendurable.

Saving precious food for others has always been a major way of expressing love and concern in China.

While she was away the truck came. I looked toward the camp and saw her running toward me, the white-golden grass surging around her blue scarf. In her right hand she carried a big colorful enamel bowl. She was running with the kind of carefulness that told me she did not want the soup with the dumplings to spill. She was still a good way off, and I could see she would not reach me for another twenty minutes or so. I did not feel I could ask the driver to wait that long, as he was already doing me a big favor. I clambered onto the back of the truck. I could see my mother still running toward me in the distance. But she no longer seemed to be carrying the bowl.

Years later, she told me the bowl had fallen from her hand when she saw me climbing onto the truck. But she still ran to the spot where we had been sitting, just to make sure I had really gone, although it could not have been anyone else getting onto the truck. There was not a single person around int hat vast yellowness. For the next grew days she walked around the camp as though in a trance, feeling blank and lost.

Because the Chinese tradition permitted little physical contact between fathers and daughters, he told me how happy he was through his eyes.

Early the next morning, [my father] went to the post office and waited outside for hours until it opened. He sent a three-page telegram to my mother. It began: “Please accept my apologies that come a lifetime too late. It is for my guilt toward you that I am happy for any punishment. I have not been a decent husband. Please get well and give me another chance.”

I also had a network of tutors who gave up their evenings and holidays happily and enthusiastically. People who loved learning felt a rapport which bound them together. This was the reaction from a nation with a highly sophisticated civilization which had been subjected to virtual extinction.

Her name was read out first; there was an awkward stirring—it was clear that people could not decide what to do. I was miserable in the extreme—if there were a lot of votes for her, there would be fewer for me. Suddenly she stood up and said with a smile, “I’d like to forgo my candidacy and vote for Chang Jung. I’m two years younger than she is. I’ll try next year.” The workers burst out in relieved laughter, and promised to vote for her next year. And they did. She went to university in 1974.

Since her return from Peking in autumn 1972, helping her five children had been my mother’s major occupation.

For years, the things to which I was naturally inclined had been condemned as evils of the West: pretty clothes, flowers, books, entertainment, politeness, gentleness, spontaneity, mercy, kindness, liberty, aversion to cruelty and violence, love instead of “class hatred,” respect for human lives, the desire to be left alone, professional competence.

To me, the ultimate proof of freedom in the West was that there seemed to be so many people there attacking the West and praising China.

The author concluded that Mao had indeed made the Chinese into “new people” who would regard what was misery to a Westerner as pleasure. I was aghast. Did he not know that repression was at its worst when there was no complaint?

I memorized the whole of the Declaration of Independence, and my heart swelled at the words “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and those about men’s “unalienable Rights,” among them “Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” These concepts were unheard of in China, and opened up a marvelous new world for me. My notebooks, which I kept with me at all times, were full of passages like these, passionately and tearfully copied out.

There was no place for [my father] in Mao’s China, because he had tried to be an honest man. He had been betrayed by something to which he had given his whole life, and the betrayal had destroyed him.

When the first black sailors arrived, our teachers gently warned the women students to watch out: “They are less developed and haven’t learned to control their instincts, so they are given to displaying their feelings whenever they like: touching, embracing, even kissing.” To a roomful of shocked and disgusted faces, our teachers told us that one woman in the last group had burst out screaming in the middle of a conversation when a Gambian sailor had tried to hug her. She thought she was going to be raped (in the middle of a crowd, a Chinese crowd!), and was so scared that she could not bring herself to talk to another foreigner for the rest of her stay.

The way [Mao] said it left no doubt that we had joined the ranks of the third world in order to lead it and protect it, and the world regarded our rightful place to be somewhat grander.

It was stated that I had violated these [“disciplines in foreign contact”] because my eyes looked “too interested,” I “smiled too often,” and when I did so I opened my mouth “too wide.” I was also criticized for using hand gestures: we women students were supposed to keep our hands under the table and sit motionless.

Much of Chinese society still expected its women to hold themselves in a sedate manner, lower their eyelids in response to men’s stares, and restrict their smile to a faint curve of the lips which did not expose their teeth. They were not meant to use hand gestures at all. If they contravened any of these canons of behavior they would be considered “flirtatious.” Under Mao, flirting with foreigners was an unspeakable crime.

Frequently in crowded buses, trains, and shops I would hear women yelling abuse at men and slapping their faces. Sometimes the man would shout a denial and an exchange of insults would ensue. I experienced many attempted molestations. When it happened, I would just sneak away from the trembling hands or knees. I felt sorry for these men. They lived in a world where there could be no outlet for their sexuality unless they were lucky enough to have a happy marriage, the chances of which were slim. The deputy Party secretary of my university, an elderly man, was caught in a department store with sperm oozing through his trousers. The crowds had pressed him against a woman in front of him. He was taken to the police station and subsequently expelled from the Party. Women had just as tough a time. In every organization, one or two of them would be condemned as “worn-out shoes” for having had extramarital affairs.

In the days after Mao’s death, I did a lot of thinking. I knew he was considered a philosopher, and I tried to think what his “philosophy” really was. It seemed to me that its central principle was the need—or desire?—for perpetual conflict. The core of his thinking seemed to be that human struggles were the motivating force of history, and that in order to make history “class enemies” had to be continuously created en masse. I wondered whether there were any other philosophers whose theories had led to the suffering and death of so many. I thought of the terror and misery to which the Chinese population had been subjected. For what?

But Mao’s theory might just be the extension of his personality. He was, it seemed to me, really a restless fight promoter by nature, and good at it. He understood ugly human instincts such as envy and resentment, and knew how to mobilize them for his ends. He ruled by getting people to hate each other. In doing so, he got ordinary Chinese to carry out many of the tasks undertaken in other dictatorships by professional elites. Mao had managed to turn the people into the ultimate weapon of dictatorship. That was why under him there was no real equivalent of the KGB in China. There was no need. In bringing out and nourishing the worst in people, Mao had created a moral wasteland and a land of hatred. But how much individual responsibility ordinary people should share, I could not decide.

The other hallmark of Maoism, it seemed to me, was the reign of ignorance. Because of his calculation that the cultured class were an easy target for a population that was largely illiterate, because of his own deep resentment of formal education and the educated, because of his megalomania, which led to his scorn for the great figures of Chinese culture, and because of his contempt for the areas of Chinese civilization that he did not understand, such as architecture, art, and music, Mao destroyed much of the country’s cultural heritage. He left behind not only a brutalized nation, but also an ugly land with little of its past glory remaining or appreciated.

The Silk River meandered past the campus, and I often wandered along its banks on my last evenings. Its surface glimmered in the moonlight and the hazy mist of the summer night. I contemplated my twenty-six years. I had experience privilege as well as denunciation, courage as well as fear, seen kindness and loyalty as well as the depths of human ugliness. Amid suffering, ruin, and death, I had above all known love and the indestructible human capacity to survive and to pursue happiness.

AFTERWORD

One place I particularly set my eyes on was the English pub opposite our college, because we were specifically told not to visit it. The Chinese translation for “pub,” jiu-ba, in those days suggested somewhere indecent, with nude women gyrating. I was torn with curiosity. One day, I sneaked away and darted for the pub. I pushed the door open and stole in. I saw nothing sensational, only some old men sitting around drinking beer. I was rather disappointed.

It did not seem strange that an embassy official who hardly knew me should bare his heart. In those years, people were so weighted down with tragedies in their lives that they were prone to unburdening themselves suddenly when they sensed a kindred spirit.

That single remark untied a strangling knot fastened on my brain by a totalitarian “education.” We in China had been trained not to draw conclusions from facts, but to start with Marxist theories or Mao thoughts or the Party line and to deny, even condemn, the facts that did not suit them.

We were not treated by our own government as proper human beings, and consequently some outsiders did not regard us as the same kind of humans as themselves.

As I listened to my mother, I was overwhelmed by her longing to be understood by me. It also struck me that she would really love me to write. She seemed to know that writing was where my heart lay, and was encouraging me to fulfill my dreams. She did this not through making demands, which she never did, but by providing me with stories—and showing me how to face the past. Despite her having lived a life of suffering and torment, her stories were not unbearable or depressing. Underlying them was a fortitude that was all the time uplifting.

My textbooks in China had been written by people who had never had any contact with foreigners themselves, and had mostly been direct translations from Chinese texts. The lesson “Greetings,” for example, gave the exact equivalent of the expressions we used in China, which were, literally, “Where are you going?” and “Have you eaten?” And this was how I used to greet people initially in Britain.

Just before [Wild Swans] was published, my mother wrote to me and said that the book may not do well and people may not pay much attention to it, but I as not to be disheartened; I had made her a contented woman because writing the book had brought us closer. This alone, she said, was enough for her. My mother was right. I had come to a new degree of respect and love for her. But precisely because I now knew her better, I could see that her professed indifference to recognition was her typical effort to try to protect me from potential hurt. I was very moved.